To Add or Not to Add: That Is Only the First Question

Many times, when clients hear the word “diversification,” they think the more assets, the better. However, not all additions to a portfolio are created equal. Measuring assets by the risk they bring to the portfolio and correlation with existing assets can have huge implications on portfolio construction decisions.

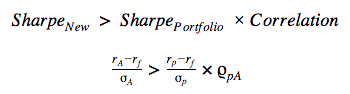

Within the CFA® program’s portfolio construction framework, there is an equation that tests whether adding a new investment into the portfolio will help improve results over time. It states that if the Sharpe ratio of the new asset is greater than the Sharpe ratio of the existing portfolio times the correlation of the existing portfolio with the new asset, then you should include it.

But let’s step back and think about why this makes sense and what investors need to consider when making this portfolio construction decision.

Diverse Correlations

First, why correlation? The more investments you make, the better diversified you are, right? Well, just because you buy stock in a lot of different companies doesn’t mean your portfolio will be immune to shocks in the stock market. At some point, the incremental risk–return benefit (or improvement in Sharpe ratio) of adding more stocks to your stock portfolio will diminish. The following chart shows how the incremental benefits of adding new stock sectors to a portfolio start to taper off at 5.

Chart 1.

(Source: Bloomberg. Portfolios are calculated by averaging returns of S&P 500 sectors. Time period: 12/31/2000–4/28/2017)

However, by including assets that have a low correlation to the stock market (or whatever assets make up your portfolio), the portfolio is better protected for different market environments. For instance, if bonds are added to a stock portfolio, they may help offset stock losses when the market goes down because bonds typically do well in recessions. Figure 1, below, shows how different asset classes behave differently depending on the phase of the market cycle.

Figure 1.

Risky Business

The other important measure to consider when adding assets to a portfolio is risk. Risk matters because it can have a disproportionate effect on portfolios. Take a classic 60% stock/40% bond portfolio—it seems like a diversified portfolio with a significant portion of bonds to help offset stock losses. But when you view it through the lens of risk, stocks are approximately three times riskier than bonds. So they make up about 90% of portfolio risk, as shown in Figure 2. Dollar-weighted allocations can paint a very different picture than risk allocations. Therefore, bonds don’t provide as much protection against stock losses as you might think.

Figure 2.

Equity moves can be so strong that they overpower bond allocations if risk levels aren’t considered. This is why the CFA equation considers return as a measure of risk by using the Sharpe ratio. The riskier an asset, the more impact it can have on a portfolio.

Risky assets can be a good thing, especially if they have a low correlation to the existing portfolio, because they can be a positive source of returns when nothing else in your portfolio is working in your favor. However, risk should not only play a role in whether you include the asset, but also how much you include. A little bit of a volatile asset can go a long way.

Building a Strategy

Take energy commodities for example: an average energy stock is a great hedge for inflation and it has a moderate to low correlation to both stocks and bonds. It also has an average annual standard deviation of 30.8% (as measured by S&P GSCI Energy Index).

This level of risk is very different from stocks or bonds, which have about 14% and 4% standard deviations, respectively (as measured by the MSCI World Index and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index). Energy has suffered historic drawdowns of close to 90%, as shown below in Chart 2. That level of volatility might be very difficult for some clients to stomach if it isn’t taken into account during portfolio construction.

Chart 2.

(Source: Bloomberg. Returns are shown excess of cash. Energy represented by S&P GSCI Energy Index, stocks represented by MSCI World Index, bonds represented by Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Time period: 12/31/1982–4/28/2017)

Even stocks, which have had instances of greater than 50% drawdowns historically, can be too much risk for an average client if they are not properly diversified. Bonds (the green line in Chart 2) are the natural diluter to very risky assets. However, if you allocate too much of a client’s portfolio to bonds, they might not meet return targets.

Instead, if you construct your portfolio with risk levels in mind, you can find an appropriate level of risk that meets your client’s return targets while also setting appropriate expectations.

Risk analysis can also help determine the most efficient assets that can help to avoid large drawdowns. Losses can still happen, but they tend to be to a lesser degree so you don’t have as much ground to make up. Additionally, clients are less likely to get nervous and pull their money out of the market (which often happens right before a rebound).

Seeking Real Diversity

Putting the concepts of correlation and risk together, we find that the best assets to add to a portfolio are those with low correlations and high risk. A truly diversified portfolio contains multiple assets that act very differently from one another (when ones goes up, the other goes down and vice versa).

Second, risk as a measure of return needs to be considered when allocating to new assets, as the Sharpe ratio equation dictates.

Attractive returns can often come along with different levels of risk. This can be a good thing for portfolios, because small amounts of risky assets can make a big difference in returns and improve portfolio efficiency through time.

But to go one step further, it’s just as important to use risk when determining how much of an asset to include in a portfolio. Portfolio managers who use this philosophy are able to tailor their decisions based on client return targets and risk constraints, as well as set the proper expectations for the clients themselves.

About the Author

Elizabeth Jones, CFA, serves as a research analyst for Invesco’s Global Asset Allocation team. Her responsibilities include investment research and modeling across equities, fixed income, and commodity markets. Elizabeth joined the team in 2016, moving from Invesco's Product Management team where she supported the Global Asset Allocation team in a variety of analytical and client-facing roles. She received her BA in mathematical economics and MA in management from Wake Forest University, and she worked with Franklin Templeton Investment Management prior to joining Invesco in 2010. Elizabeth has been a CFA charterholder since 2014. She is a member of the Invesco Women’s Network, CFA Institute, and the Atlanta Society of Financial Analysts.